Godmorgon världen

En dikt

This is a more curated feed of things I am more proud of, in some arbitrary way.

En dikt

Phenomenology is the study of the phenomena we experience. Taking a step back from the way we normally perceive the world, the filters and abstractions that make it possible to live in it, phenomenologists try to perceive the information their senses provide as directly as possible. This makes it a very subjective study with findings that are hard to generalize, and that’s part of the point. How boring wouldn’t it be to live based solely on generalizable undisputed facts? Phenomenology is one of many ways to produce knowledge that isn’t trying to be objective.

My thoughts after reading half of the Malazan Book of the Fallen series

A poem about abstraction

It was the second spring of the year, or perhaps third. I can’t remember. Where I live the transition from winter to spring doesn’t go smoothly, it is a tug of war and spring has to try multiple times in order to succeed. (sidenote: This was not the last spring of the year. In a feint to tug at our collective hearts, the spring decided to yield to winter one last time. Only days after it was snowing again and temperature dropped down to -8 ℃. I had foolishly put my trust in the weather and biked to school in spring clothing. That was a mistake I will surely make again.1 ) In any case, a combination of switching to summer time and good weather meant that the sun shined brighter compared to before, the contrast making me feel like I was newly awake. When I think back to the days before it is as if I saw the world through a black veil, and only now had I taken it off. The sky was intensely, almost imposingly blue, and the snow was mostly white without much slush. Pristine early Swedish spring.

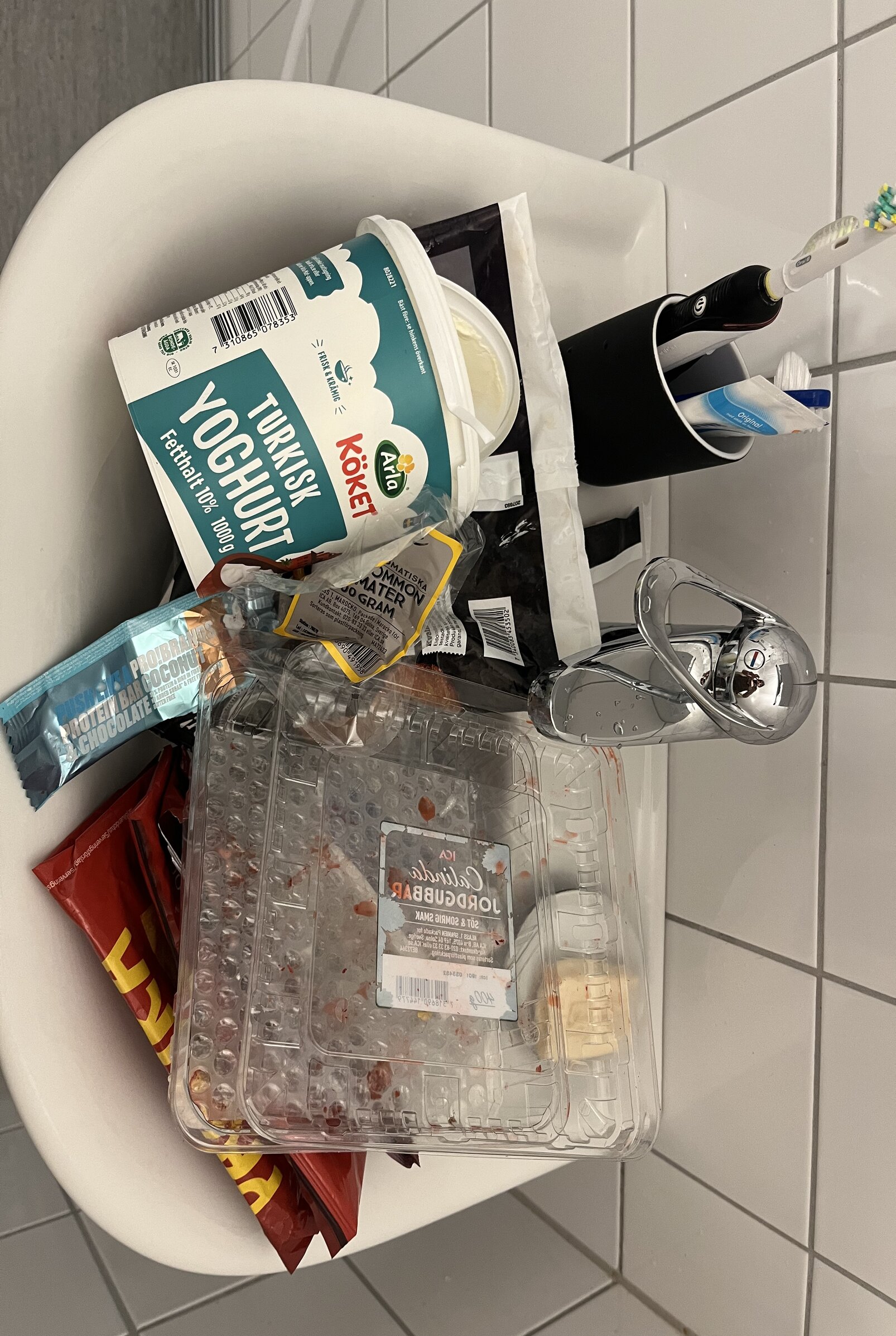

How much trash do we produce every day?

How and where do we notice trash?

When do we find trash disgusting?

How could we become more conscious?

And, finally: What is trash at all?

A poem about traffic lights

A poem about ice

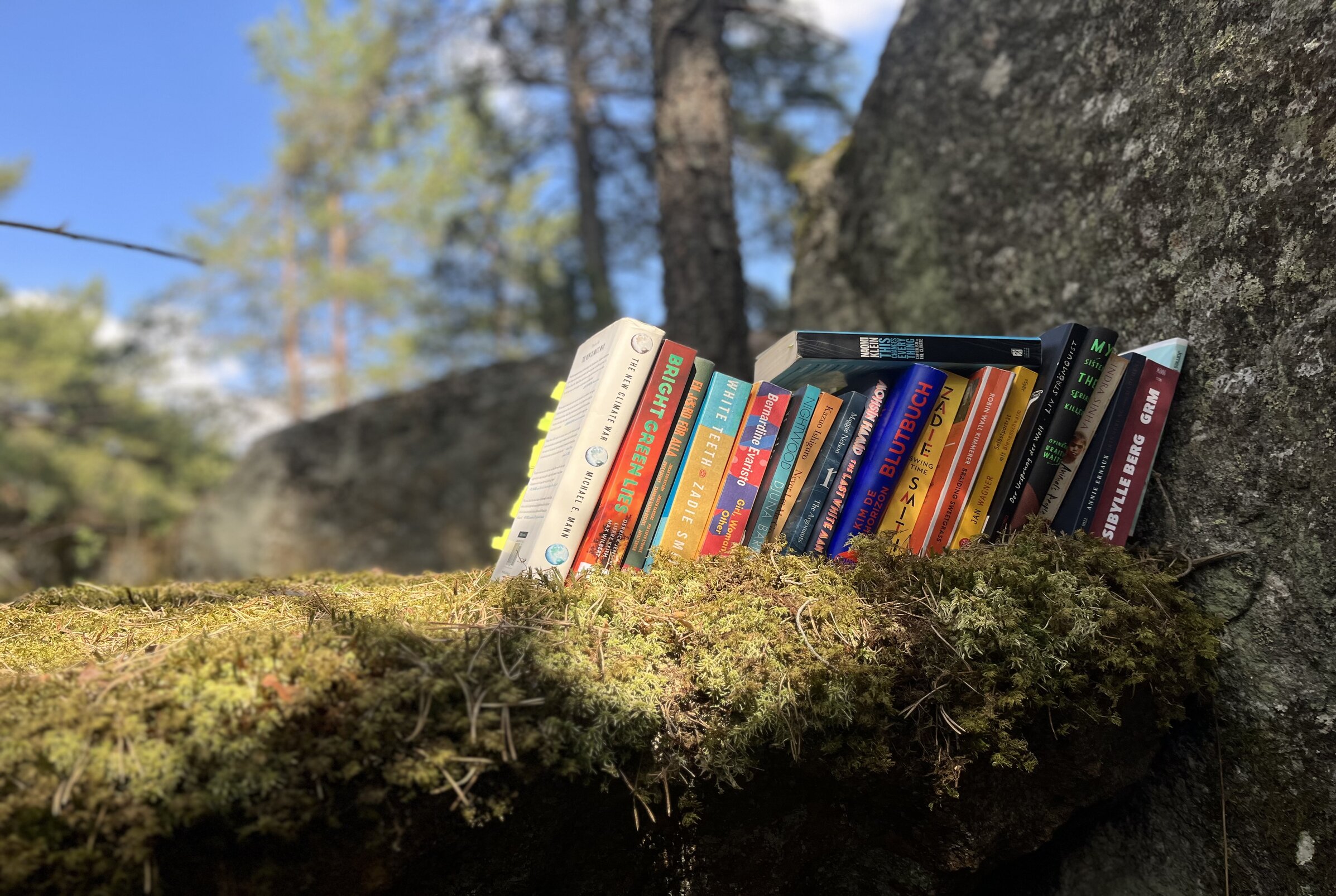

Nassim Taleb often says crazy things (like saying that mathematics is bad because economists misuse it), but sometimes he says something useful. One such thing is the Antilibrary: the collection of books in your library that you haven’t read. He values these books more than the read books because they are a reminder of how much you don’t know, a form of intellectual humility before the copious amount of knowledge in the world (Taleb 2008). (sidenote: Something Taleb himself would benefit from having more of honestly.1 )

Sometimes there are papers that are interesting, have a simple core argument, but are nevertheless hard to approach (perhaps because of added nuance or rigour requirements). “Democratic Theory and Border Coercion: No Right to Unilaterally Control Your Own Borders” by Arash Abizadeh is one such paper that I will attempt to distill down to it’s core below. For more details, elaborations and the impacts on the self-determination argument I refer you to the full paper.

I think there is something special about The Malazan Book of the Fallen’s magic. It’s honestly hard to put it into words, but I think it is something to do with how inseparable the magic is both from the world and from the text itself. The magic doesn’t feel like a system, it isn’t just the physical effects that affect the world. No, the whole world is magical and can’t be neatly separated into a ‘system’ and a ‘place’, nor can the magic be disconnected from the prose itself. Magic is created in the metaphors, in the names, in the subtext, as a part of the prose. Much of the plot and magic occurs in that place in between the lines, and are as such part of the form of the text. It’s not neatly articulable because it’s a bundle of words, associations, implications and imagery. It is not abstract.

Hur har synen på teknik förändrats över tid? Det är förstås en väldigt bred fråga som jag inte har plats, tid, eller kunskapen att besvara. Istället har jag valt att rikta in mig på två idéer som som jag observerat bli uttrycka: elektrifiering som lösning på bilars (alla) klimatproblem, och effektivisering som medel för att minska utsläpp. Vad finns det för historisk bakgrund för dessa idéer? Vilket syfte har effektivisering haft genom historien och vilka konsekvenser har teknokratisering?

A spoilerfree exploration of a hidden villain in the volleyball manga Haikyuu.

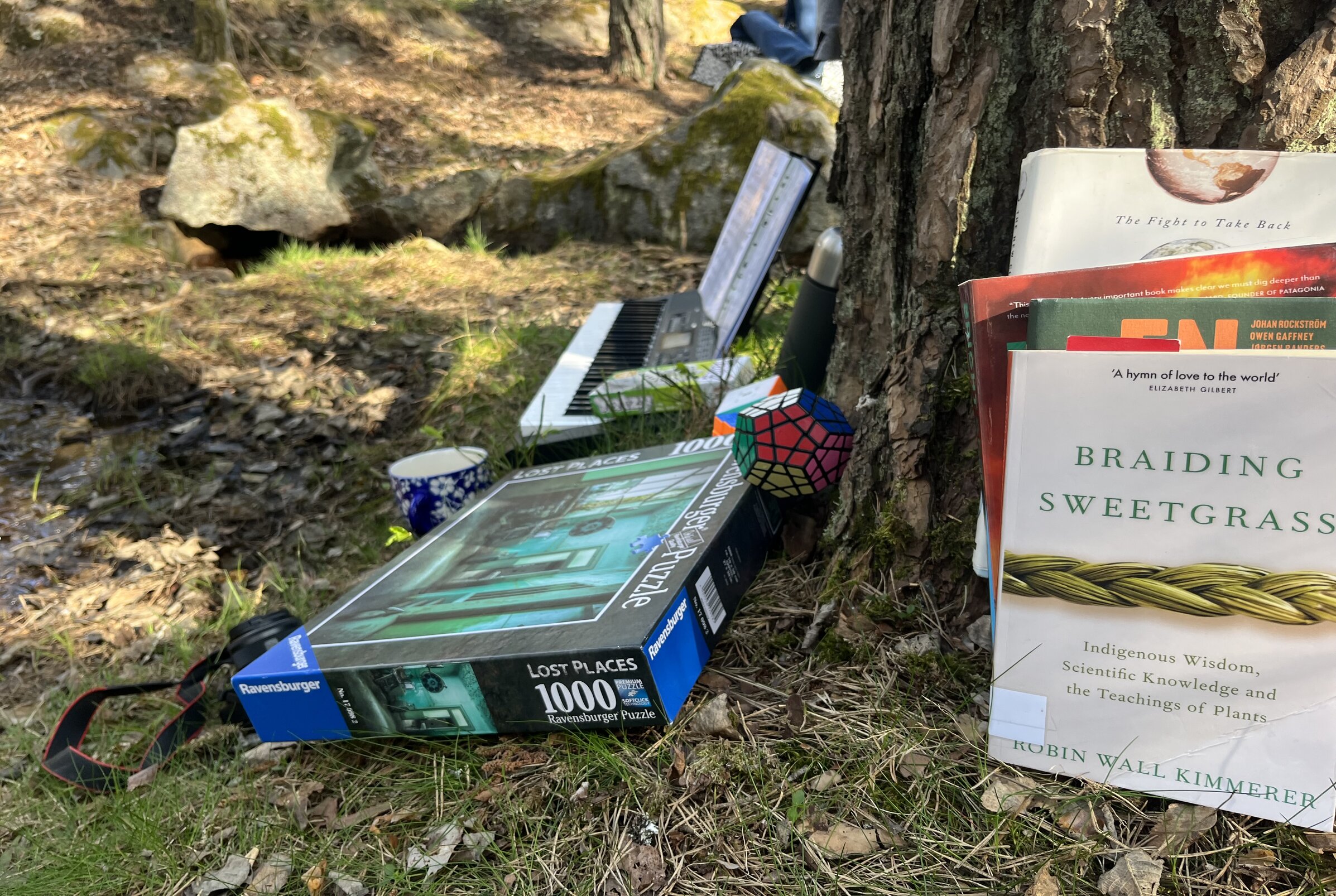

In order to improve my sleep schedule I’ve picked up the habit of reading a bit before going to bed. It becomes a ritual that helps me ease into sleep. This however, places some constraints on the book as getting excited is counterproductive to the goal of relaxation. The book can’t get too boring either as the goal is to be able to read a book, and boring books are no fun to read.

This is a translation of my other post: En berättelse om berättande

I don’t think I’ve had a reading experience like the one I had with Lev Tolstoy’s War and Peace before. (sidenote: The version I have isn’t the one that is most widely known. Tolstoy apparently completely rewrote the book and it is that version that was published in 1867. It wasn’t until 2000 that the original version would be published in Russian as an ordinary novel. I haven’t been able to find it in English, but my copy from 2016 says that work is being done to translate it. The biggest change seems to be that this original version ends around 500 pages earlier. (Tolstoj 2016) ) The end of the book made me reconsider what the entire book was about, but the interesting thing is that it didn’t happen because of a plot twist or any other concrete events that occur. My view of what had happened didn’t change either like how a good plot twist makes you reinterpret the events that had happened before. No, both the reason for and the subject of my new interpretation is the style the book is written in, the state of the characters, and what the narrator chooses to focus on. Most of the events — the countless conversations and gossip, wars that are fought over arbitrary reasons, and romances that spark and fade away — feel pretty meaningless and uninteresting, but after finishing the book I’ve realized there is a meaning behind this meaninglessness. The concrete events are still irrelevant, but the superficiality that the introduction brims with slowly fades away until it is completely discarded towards the end where the narrator scornfully denounces it. It is this change of narration that in hindsight has captivated me.

A translation of this post exists here: A story about story telling

Jag tror inte jag har haft en läsupplevelse som liknat den jag haft med Leo Tolstojs Krig och Fred förrut. (sidenote: Den versionen jag har är annorlunda från versionen som är mest känd. Tydligen skrev Tolstoj om romanen och det är den som sen blev publicerad i 1867. Det var inte förrän år 2000 som den ursprungliga versionen blev publicerad som en vanlig roman på ryska. Största skillnaden verkar vara att den här versionen är 500 sidor kortare där framförallt den avslutande delen är stramare. (Tolstoj 2016) ) Slutet av boken fick mig att tänka om kring vad resten av boken handlade om, men det intressanta är att det inte skedde på grund av någon tvist, eller egentligen något annat konkret som händer i boken. Inte påverkades heller min syn på vad som hade hänt, likt hur en bra tvist får en att tänka om kring allt som har hänt hittils. Nej, både orsaken och subjektet till min nya tolkning är stilen som boken är skriven i, tillståndet som karaktärerna befinner sig i, och vad berättaren lägger fokus på. Mycket av det som händer — oändligt många samtal och skvaller, krig som utkämpas av godtyckliga anledningar, och romanser som blossar upp och klingar av — ter sig meningslöst och ointressant, men efter att ha läst klart boken har denna meningslöshet fått en ny mening. Det konkreta i dessa händelser är fortfarande ovidkommande, men ytligheten som inledningen är fullkomligt överflödig av glider sakta iväg under bokens gång, tills den fullständigt kastas bort mot slutet där berättaren föraktfullt tar avstånd från det. Det är denna förändring som nu i efterhand har fångat mig.

The first time I stumbled upon the book Invisible Cities, when it was used in the video essay “Searching for Disco Elysium”, I didn’t really take notice of it. [1] [1], [2] The book played a secondary role, it was used to highlight an aspect of the titular game Disco Elysium, so it was perhaps unsurprising that it didn’t strike me as something remarkable. However, that changed when I read the essay “Two Concepts of Legibility”. [3] It used Invisible Cities in a similar way, to make a point about the legibility of software, which made me wonder if there was something special about it. Why was it that two very different essays, one about media critique and the other about philosophy of software design, could use it so effectively?

In this tutorial I will go through the ideas that underpin constraint programming, a technique for solving hard algorithmic problems. It is a pretty advanced technique and is an active research area, but despite this the core ideas are actually surprisingly easy to understand. After reading this tutorial hopefully you’ll understand the principles of how a constraint programming solver works.

I want this tutorial to be understandable to as many as possible, regardless of how much programming background you have. If you feel like you don’t understand it’s probably not your fault, but mine. I’ll try to make it clearer if you tell me about it (for example on the mailing list). At times the text can be a bit technical, but I try to explain things from different angles so try continue reading if you get stuck and it will hopefully be clearer.

I’ve been reading Dune and it’s shaping out to be one of my favourite books, but one thing in particular stood out to me: the characters are boring. How can a story be this good with boring characters? For me the answer is that the focus and enjoyment lies elsewhere: partly in the political intrigue between different factions, but mostly in the exposition. The exposition is so good!

One reason that I wanted to read Speaker for the Dead again was because I heard people say that the author was a massive racist, which is interesting because the same people would say that his racism conflicts heavily with the themes of the book. (sidenote: If you want to read this book, I encourage you to do so in a way that doesn’t support him financially, such as borrowing it from a library, a friend or from the seven seas. ) The second reason was that most people seem to like this book the most out of the Ender’s quartet, whereas when I read them last time I liked the last two books more. I think this is because I had a hard time enjoying books where the relationships between people are central. Instead I would get the most enjoyment when new science was introduced and explained, similar to how I would enjoy pop science magazines. Today I like to think that I enjoy a wider range of books, even fluffy nonsense ones about compassion and understanding one another. Reading Speaker of the Dead could confirm this hypothesis and also see what it was that others saw and I missed when I first read it.(sidenote: Then there was the third reason which was that I already had the book and didn’t have anything else to read, but let’s not talk about that. )

Unseen Academicals, a book in the Discworld series by GNU Terry Pratchett, is about the wizards of Unseen University playing football, which the front of the cover helpfully suggests. The back of the cover on the other hand informs us that ‘The thing about football — the important thing about football — is that it is not just about football’. And sure enough, while Unseen Academicals is about football, it’s not just about football. It is also about, perhaps unsurprisingly to seasoned Pratchett readers, learning to accept and be proud who you are despite what preconceived notions and stereotypes exists around you. I wouldn’t be surprised if lots of queer people saw themselves in this book.

This contains spoilers for the some character developments and the general structure of the Golden Age Arc of Berserk. Berserk is an extremely well crafted manga which I highly recommend. I think it would be best to read that first, although I think it is very enjoyable (maybe even more enjoyable) on second reading so I don’t think these spoilers would hurt the experience too much.

In her video on Tragedies, Red from Overly Sarcastic Productions defines and describes the formula of the ancient Greek Tragedies. It’s a great video which I reference a lot here that I recommend watching. All general descriptions about how the Tragedies work comes from that video.

This contains spoilers for the some character developments and the general structure of the Golden Age Arc of Berserk. Berserk is an extremely well crafted manga which I highly recommend. I think it would be best to read that first, although I think it is very enjoyable (maybe even more enjoyable) on second reading so I don’t think these spoilers would hurt the experience too much.

In her video on Tragedies, Red from Overly Sarcastic Productions defines and describes the formula of the ancient Greek Tragedies. It’s a great video which I reference a lot here that I recommend watching. All general descriptions about how the Tragedies work comes from that video.

I discovered in high school that I like to write, which came as a surprise because I had always disliked writing assignments. With this newfound knowledge I tried to explore writing as a hobby. The only way I had written anything before was for larger projects, writing assignments, and that was what I tried.

My first project was about the movie Spirited away. I had noticed that some side characters, the big baby and the faceless monster, went through their own story arcs parallel to Chihro’s. I took some notes and began planning the layout for the text, and then I got stuck. The scope and goals I had set up for myself were too large and I didn’t know how to fulfill them. After I realized that project was dead I tried again with some other topics but they all failed the same way.

I have used org-mode for a few years now, primarily for task management, document writing and note taking. It has been very good for keeping track of what I need to do in my studies and volunteer work, but despite this I’m moving away from it for my task management.

I find it very hard to think actively, as opposed to reactively, when I’m at a computer. For example writing a new text is harder to do on a computer than with pen and paper, but editing a piece of text works fine. I’m not sure why this is, but I think one reason is that I feel like I constantly have to do something when I’m at the computer, as if the computer demands a response from me.

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro is perfect for you if you are an science fiction reader looking to branch out into more conventional stories. It is still a sci-fi, but not the kind that builds a story around a question such as “How can a great galactical empire collapse?” or “How would/should humanity react to the invention of intelligent robots?”. Ishiguro doesn’t rely on exposition to explain the world or what is special about it. There is no reader surrogate who can ask the necessary questions or a narrator that explains what is needed. Instead he just tells the story through the perspective of a person living in that world, never explicitly explaining how the world works because that is common knowledge there. Hailsham, the orphanage that the main character grows up at and the setting for a majority of the book, seems very normal. It might as well exist in our world, but as the story progresses we begin to understand how it is different by reading between the lines. By the time the big explanation is given by one of the teachers both we the readers and the main character have already figured out the broad picture, it is merely a confirmation, a crystallization of what we already knew.